How do consumers value organic groceries?

I used python to compare prices between organic and conventional grocery items.

- Prices are a great measure of what makes a product different.

- Organic products have always commanded a premium.

- That premium measures how shoppers value the organic difference.

The approach:

I spend too much time in the supermarket comparing prices between conventional items and premium options. This is an absolute joy, but it lacks breadth and depth. Approaching this instead as a data science question, I built a program in python to query Kroger’s Open API. I pulled product data for 11k items listed in a single Cincinnati, OH, location. Within that dataset, I was able to identify 206 like-for-like, lowest cost organic and conventional product pairs. Using these pairs, I calculated a percent premium to indicate how consumers value each organic item versus its conventional counterpart.

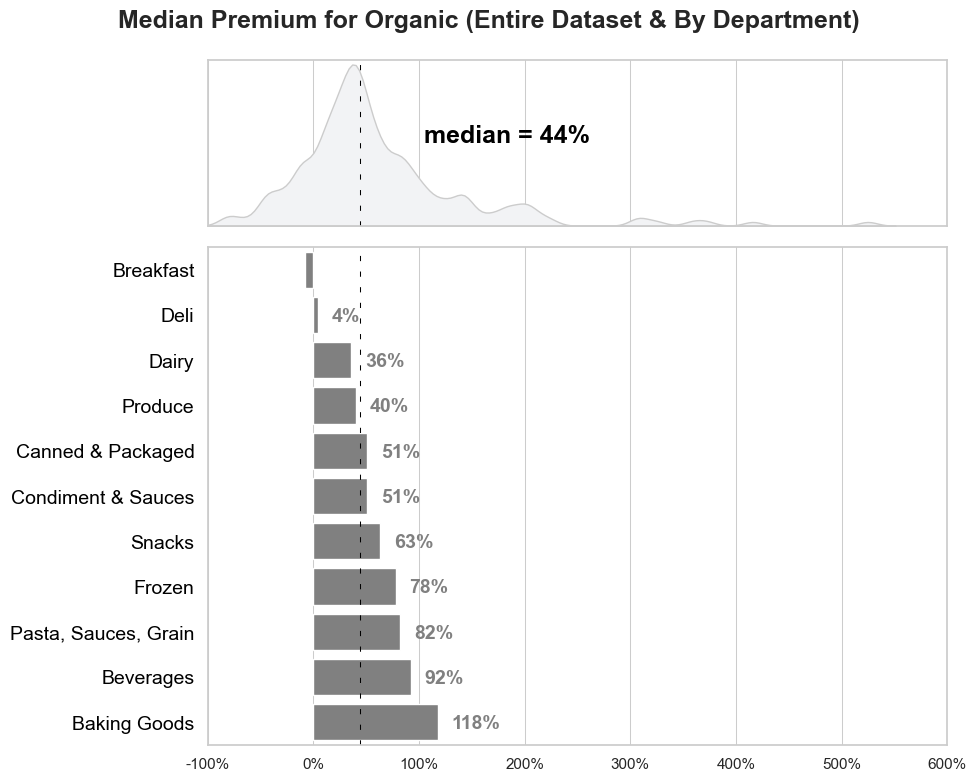

The median organic item sold for 44% more than conventional.

The produce aisle as a whole drove the median in this dataset. It hosted the largest variety of organic items with the majority of premiums falling between 35-55%. A big surprise: median premiums for snacks (63%), frozen goods (78%) and baking goods (118%) indicate that shoppers–what could be driving that?

A few things could be going on here:

- I don’t know enough about produce retailing, but this store might use high quality affordable produce as a way to draw shoppers into the store while recouping margin in other aisles.

- Story matters. Organic produce pricing might be more competitive becuase a produce sticker does not afford much space for storytelling (so price plays a larger role in the purchase decision).

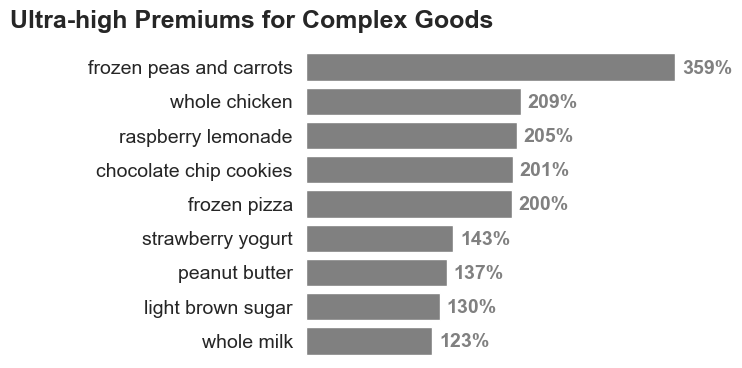

So what would compel a shopper to pay 2-3x the price of conventional?

My best guess: premiums are compounding. The more premium attributes a product includes (ie the more complex it is) its price point will be exponentially higher.

Frozen pizza is a great example.

As a convenience item, demand for frozen pizzas may be more inesalstic than other items. Shoppers buy frozen pizzas less frequently, so paying more for something special has less of an impact on their monthly spend. Further when shoppers choose an organic frozen pizza, they opt for organic cheeses, organic tomatoes and many more organic ingredients. Each of those ingredients builds a story–organic vine-ripend toomates and dairy cows that spend more time on pasture grass make better tasting pizza. The value of those stories compound, and we find organic frozen pizza on shelf 2x the price of conventional.

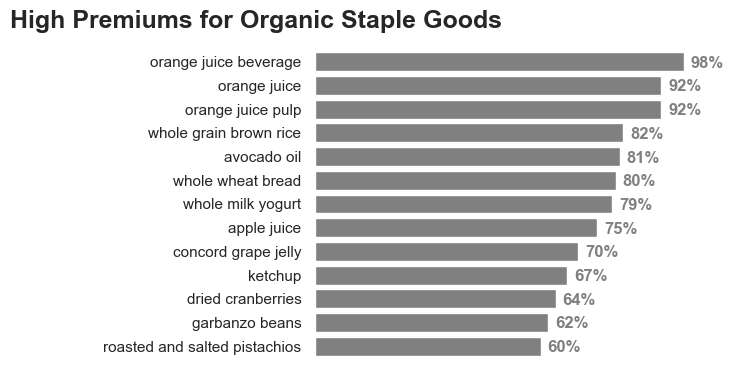

The biggest opportunity for value creation: premium staple goods.

I find the products with premiums ranging from 50-100% most compelling.

Unlike the ultra-premium products, these represent a class of normal staple goods–the goods shoppers purchase and consume on a weekly basis. Volume multiplied by relatively high premiums makes this group the biggest value driver in a standard grocery list.

Loyalty defines these products.

If a brand can tell the right story, shoppers will see the value and stick with a brand. I buy a certain brand of organic milk because I am a nerd. I care too much about grass and fat. But I also buy that organic milk because the people I love tell me it tastes better. The brand gives me a short story right on the carton about how they do things differently to make sure their milk tastes better. There is no going back.

A look forward:

- Shoppers value certified claims. Using USDA as a foundation, let’s continue to build robust transparency programs that tell great stories.

- Let’s build value in everyday pantry staples. Competition is steep, but if we make something unique and tell a great story, shoppers will place our brand (not just the commodity name) at the top of their grocery list.

About the data project:

How I isolated each item pair:

- I parsed product names to determine whether a product is organic or not. USDA Organic regulations state that only certified organic products may be described as “organic”, so it is safe to assume a product listing “Fresh Organic Fuji Apples - 2 pound bag” represents a certified organic product.

- I parsed the product name field once again to isolate a “common name” for each item. In the example above that would pull “fuji apple” from “Fresh Organic Fuji Apples - 2 pound bag”.

- And finally, I converted all fill weights into uniform units of measure (either pounds or fluid ounces depending on the physical product type).

- With these three helper columns, I was able to group items by organic status and common name. And within each grouping, I was able to isolate the lowest $/lb or $/fl oz variant.

- This yielded two dataframes: 1.) the lowest cost organic variants and 2.) the lowest cost conventional variants. I joined these into a single comparison dataframe to calculate premiums.

Example calculation: organic fuji apples priced at $2.64/lb vs. conventional fuji apples priced at $1.83/lb results in a 44% premium for organic. Right in line with the median–what an indicator!

One source of error: bulk deals (high fill weight, low unit price) created some big outliers. To reduce sticker shock organic items often sell in smaller configurations. And conversely, we see more bulk discounts on conventional items. When these converge, my comparison produced an outlier.

A limitation: to generate common names for each item, I used string matching with regex. In future iterations of this project, a natural language processor paired with a machine learning model could: Find more matches and increase the sample size Analyze product titles to extrapolate premiums not just from organic claims but other claims as well such as non-gmo, regenerative and combinations thereof.